Translation:

The first woman crossing Greenland: the adventurer Myrtle Simpson

“Bad mother who puts her children in danger,” was the headline after Myrtle Simpson’s Greenland crossing

She went on an expedition with her husband and baby. And she was the first woman to cross Greenland. Today Myrtle Simpson is 90. In conversation with Claus Lochbihler, the Scottish woman tells about her adventurous life – and gives tips for staying fit.

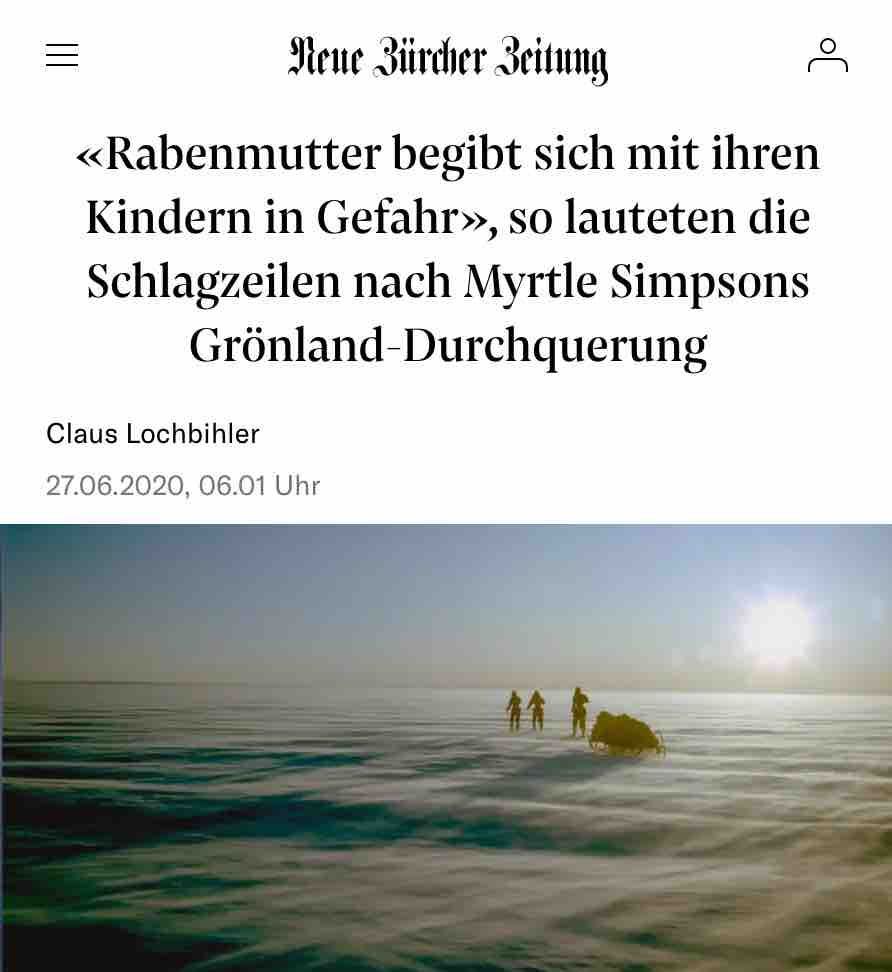

Photos: The Greenland ice sheet in all its beauty. Myrtle Simpson says it looked like there were diamonds all over the floor because it just glittered everywhere. It was an almost «heavenly experience». – Below: Myrtle Simpson in the late 1950s.

Photos by Hugh Simpson

• You were the first woman to cross Greenland on foot and on skis in 1965, followed in 1969 by a large expedition to the North Pole. You were celebrated and at the same time offended as a supposedly bad mother to your four children. Was it important for you to show that women and mothers can also be successful on an expedition?

No. I didn’t climb the mountains and later went to the Arctic to show what women can do that. I went because I liked it.

• Where does this enthusiasm for mountains, ice and wilderness come from?

It probably has to do with my early childhood. My father was a British officer in India, on the border to Afghanistan. In the summer, all Britons fled to the mountains to escape the heat. One of my earliest but strongest memories comes from that time. I sit in a basket on the back of a donkey and stare wide-eyed at the mountains, the ice and the snow.

• After the war and the independence of India and Pakistan, you returned to Scotland, to Edinburgh, your father’s home.

I stuck out there like a sore thumb. Do you know that expression? Anyway, Edinburgh was a narrow and stiff city. I was different and didn’t fit it because of my childhood in India and because I didn’t have a great school education. But near Edinburgh there are mountains, actually hills, the Pentlands. I was hanging around there. First hiking alone. Until one day I met climbers at a rock. They became my friends.

• Was your future husband there too?

Yes, but he was just one of many at the time. It was the way it is everywhere where people climb: we were a small close group where everyone was friends with everyone. I was the only woman. Back then in Edinburgh, it wasn’t appropriate for women to climb.

• Did you wish there had been more women like you?

I had my girlfriends. But I was never drawn to the women’s climbing clubs. Maybe because I always had enough climbing friends to go with. The women’s climbing clubs were founded at the end of the 19th century because some men did not want to climb together with women. And because many clubs only allowed men. But I never had this problem.

• Soon after, you went to Fort William, the western Scottish Highlands. Why?

Because that’s where the big mountains are in Scotland. I found a job as an X-ray assistant at Fort William Hospital. My boss, Ian Duff, was not just a doctor, he was a mountaineer and a pioneer in mountain rescue. He was working on his “Duff Stretcher” – a stretcher specifically for the mountains that could be lowered like a sled. It was standard for a long time. When the weather was nice and there was nothing going on, we went to the mountains to test some changes in this stretcher. I was on Duff’s team. That’s why the climbers accepted me very quickly and took me with them.

• Mountaineering boomed in those years. . .

Yes, after Edmund Hillary climbed Everest in 1953, everyone wanted to go higher and higher. Preferably in the Himalayas. But that was very expensive back then. And after World War II, Britain was no longer wealthy. There were slums and not enough work for the hundreds of thousands of soldiers returning from the war. But emigrating was cheap. A trip to Australia and New Zealand cost ten pounds. I was one of those Ten Pound Poms, as the British emigrants were called. In my case, I went to New Zealand in six weeks by boat. Not because I wanted to start a new life. But to go climbing.

• How was it?

It was wonderful. In New Zealand there were countless ascents and routes that had never been climbed, but only a few climbers and mountaineers. Almost as if Edmund Hillary, who was New Zealander, was the only alpinist there.

• Nevertheless, you returned to Scotland and went to the Andes in 1958. What made you go there?

We had seen pictures that French climbers took of the Andes: unclimbed, beautiful, high mountains! Not as high as in the Himalayas. But you didn’t need expensive permits for the Andes. And the journey was easy: we went to Peru by boat, then by train, finally a bit on foot, and we were already in the Andes. We got some money from the British government – they had something to spare for expeditions after climbing Everest.

• Was your future husband there too?

His time as a researcher and expedition doctor in the Antarctic came to an end. So we met in Peru. It came from the south, we – our climbing friend Billy Wallace and I – from the north. And then we had six months in the Andes.

• You got married after your return. . .

Yes, Hugh and I had known each other from climbing before Peru. Hugh was a pathologist. And he did research. Back then there was a lot of research funding from NASA for scientists to find out how people react in extreme conditions. NASA wanted to know if and how humans could survive in space and on the moon. That was what Hugh was researching too. Not in space, but in the Arctic and Antarctic.

• You then accompanied him on his expedition to Svalbard. It was absolutely unusual at the time: a pregnant young mother who went on an expedition with her husband and a baby. What drove you?

I didn’t want to stay home. I was just too selfish for that. Besides, I didn’t know it any other way as my father in the British Army and my mother had done the same. So we – I and my son, who was eight weeks old at the time – traveled to Svalbard. I would never have thought not to do it. Also because the Sami do the same in the far north of Scandinavia: They follow their reindeer. They move on even when a child is born. So everyone just comes along.

• Did you later take your children with you as far as possible?

Yes, it was normal for my husband and me. Of course we didn’t take them on the Greenland crossing or on the North Pole expedition. But often as far as the starting point. And in the meantime they were staying with friends or with locals and were waiting for us at the end of our expedition.

• You were fiercely criticized for this in the press.

Very much! “Bad mother puts her children in danger,” was the headline. But the children were fine. Overall, we spent more time with them than without them.

• Did you as parents learn anything from the Inuit in Greenland or the Sami in northern Scandinavia?

Of course. At the beginning I carried my son in a backpack. Until I saw how women in Lapland do it. With a Komse, a birch wood cradle that was easy to carry on the hips, but that could also be attached – for example on a sledge. The perfect equipment to carry a baby safely and comfortably. When they realized that we were interested in it and were not arrogant know-it-alls, they gave us one, which I then attached to my backpack frame. We wanted to give them money to pay for it, but they didn’t want any. They had their reindeer.

Photo: On the Greenland Expedition in 1965, Myrtle and Hugh Simpson were traveling with two friends, Roger Tufft and Billy Wallace (pictured). After the adventurers were dropped off the boat, they first had to march over the sea ice in order to reach land.

• What other equipment did you have? Back then, there wasn’t a lot to choose from

We got our skis in Norway, the country of Fridtjof Nansens. Have you ever read Nansen’s books?

• Not yet.

But you should. Nansen is my hero! He was not only the first to cross Greenland over the ice in 1888, but also a great thinker and scientist. But also a very pragmatic person. When he was out, he always asked farmers and locals how they got around in winter. And he took Sami with him on his Greenland crossing because they knew how to deal with cold and snow.

• Did you study Nansen because of the equipment?

As well. Of course we had much better gear than he did. His clothes and those of his companions were still made of furs and leather and were quite heavy. It probably weighed twice as much as ours, which was made of nylon, windproof and light. Compared to today, of course, that was also a joke. Today all the clothes you need for an expedition to the North Pole fit in a light backpack.

• What were your children wearing?

Back then there weren’t any clothes for children available. So we drove to a textile factory, put our children on the fabric, and a seamstress cut the fabric around them. Today you just go to a sports shop. And the selection of mountain clothing for children is overwhelming.

• Why didn’t you use sled dogs when crossing Greenland in 1965?

My husband Hugh had spent three years in Antarctica as an expedition doctor. They also kept sled dogs with them. He knew it took about a year to set up and train a good dog team. We didn’t have the time. It was also a British tradition to go without dogs. When we stopped at one of the places at the beginning of our crossing, the residents asked: “Where are your sled dogs?” They found it very, very funny that we pulled the sledge ourselves.

• Until you turned the sled into a small sailing ship. . .

Following the example of Fridtjof Nansens, who was the first to cross Greenland in 1888, we set a small sail after we had overcome the mountains. So about halfway there. Navigating the huge ice sheet was like an ocean.

Photo: On the Greenland Expedition in 1965, Myrtle and Hugh Simpson were traveling with two friends, Roger Tufft and Billy Wallace. The sled was made entirely of wood so that no metal parts could rust. In the back you can see a bicycle – “the odometer” of the expedition.

• How long was the distance you covered each day?

We had calculated that we had to do an average of 12 miles a day, or about 19.3 kilometers. The first three or four weeks we only covered 3 miles. That was due to the difficult terrain, but also due to the temperatures. It was much warmer here than in Nansen’s time. That’s why the sled didn’t move so well. I think those were the first signs of global warming, even if we didn’t know it yet.

• What did you eat during the 36-day crossing?

The polar researchers who did the crossing before us, ate what the locals in Greenland ate too: whale and seal meat. And canned goods. We were lucky because freeze-drying was developed at that time. Ultimately on behalf of NASA – for the astronauts. We had access to such a project through Hugh, who was at university. The researchers were happy to have guinea pigs. So we bought steaks that they had freeze-dried for us.

• When you finally reached the west coast, one of your three expedition partners set about getting the first flowers. . .

That was Billy Wallace’s crazy way to be happy. Because this plant was living proof that we had the Greenland ice sheet behind us. I remember exactly what he was chewing there: the opposing saxifrage. You can find it everywhere and on the high mountains. Often this is the first plant you see when you come out of the ice.

• Four years later – in 1969 – you wanted to go to the North Pole. However, you did not reach it. Why?

Unfortunately we had to turn back. The battery system for our radio caught fire. And without electricity there was no radio reception and no time. And therefore no navigation. We would have wanted to meet Japanese scientists on a submarine at the North Pole. Without navigation we would have missed it. We would not have known whether we would have reached the North Pole even if we had been there.

• Was the food supply also a factor?

We had enough food with us. But not quite enough to walk past the North Pole.

• Did everyone in the group agree to turn around?

We argued about it for three days and three nights. My husband wanted to turn back. He was a scientist and represented reasoning. I wanted to go on. Roger Tufft, the third in the group, was first on my side. Until he joined my husband’s side because he thought we should turn around and try again. In the end it was 2 to 1 against me.

Photo: Myrtle Simpson at the North Pole Expedition, 1969.

• Didn’t that lead to a crisis in your marriage?

Being married never mattered on expeditions. We were just participants in an expedition. The only difference were the sleeping arrangements. We had one big sleeping bag for everyone. So Hugh and I slept on one side and the other participants on the other.

• You were always the only woman on the team in the Andes, crossing Greenland and trying to reach the North Pole. What was your role there? Was it different from the men’s?

Yes. Because in every good team everyone brings something special, individual.

• What did you bring to the team?

For example, I had the smaller and more skillful hands – even in the freezing cold without gloves. If you have ever used a gas stove, you know that there is a lot of fiddling around when something needs to be changed. At minus 45 degrees you can only be without gloves for a very short time. You have to be quick and clever. Physically, of course, the men were stronger. Nevertheless, women can be as good polar adventurers as men – because the most important thing is the matter of mind anyway. You have to stay focused and not let yourself go. Women are particularly good at this.

• When you see today’s expeditions with helicopters, satellite phones and carriers: do they seem less adventurous than what you did at the time?

Of course! Even Everest has become a mass target. People pay a lot of money to climb to the summit on a fixed rope with the help of guides and sherpas. This is no longer how we went on adventures in the 1950s and 1960s.

Myrtle Simpson: Stations of an Adventure

Map basis: © Openstreetmap, © Maptiler

India

Scotland

New Zealand

Svalbard

Greenland

North Pole (reversal)

• You are also considered the “mother of Scottish skiing”. Do you still ski today?

Yes, of course. I am a member of a ski club. Our championship is held annually every Saturday before Easter.

• This year too?

Unfortunately not. There was not enough snow. Furthermore, we couldn’t have organized it anyway because of the corona crisis and social distancing.

• Too bad . . .

Yes. I would have loved to come across George Stuart again. He is the only one racing in my age group. He turned 100 this year. He had to learn to ski almost overnight during World War II. He had escaped from a prisoner war camp. When farmers hid him in the mountains of northern Italy, they said: You have to learn to ski, otherwise you cannot hide and escape from here. So he learned to ski.

• Where are you now, during the corona crisis?

At home. Alone. We old people have to isolate ourselves so that we don’t catch the virus. The nearest shop is eleven kilometers away. I am fine being by myself, as I am used to it. And compared to the time in the Arctic, I’m not all alone. That time there was nobody there except us. Nobody at all.

• When did you feel most lonely there?

When we found ourselves on a huge ice floe after we had to turn around on our North Pole expedition. An ice floe drifting towards the open sea. If you look at open water and do not know whether the bridge to land is freezing again: you will feel lonely. We were lucky that it froze again.

• Is your husband still alive?

Hugh has been in a nursing home for several years now. It was hard that I wasn’t allowed to visit him for so long because of Corona. But of course I understand that they had to do everything they could to prevent the virus from entering the nursing home. We had regular calls, sometimes by video. It would be nice if he could be with me and if he was mentally fit as he used to. As a former doctor, he could answer my questions about this pandemic.

Photo: In 2017 Myrtle Simpson was awarded the prestigious “Polar Medal”. The picture also shows her husband and expedition partner Hugh Simpson (in a wheelchair) as well as a son and a daughter.

• Can you apply what you learned on your expeditions today?

Of course. If you live in isolation, you need a regular rhythm even more than usual. Like on an expedition. Most important, you can’t let yourself go. Also reading has always helped me.

• What are you reading?

Always the classics: Charles Dickens, Joseph Conrad, the great Russians. Friends sometimes throw current books into my mailbox. But I don’t know what to do with most of them. I often put them away after having read two pages. Today I threw five out of my bedroom window. I prefer to read Dickens. We already had his books with us on an expedition. I always shared a book with Roger Tufft, who joined the North Pole expedition. Once one had read a chapter, we passed it on to the other one. Hugh, my husband, was big on reading. Perhaps he took a medical study with him.

• Do you have a personal tip for staying fit?

Use it or lose it. When your strength fades, it is easy to let yourself go, to become comfortable. But this is the wrong approach! You have to keep going. And keep up what you have a nice expression for in German. You have this wonderful word. . . Wander. . .

• Wanderlust?

That’s it. I would have to use ten sentences to express what is meant by that one word.

• So you’ve kept the wanderlust, the drive to discover new things? Even at 90?

I think everyone has it in them. But if you live too compliant, always in your small world, always doing what everyone expects, it gets lost.

• Do you already have plans for what to do after the Corona crisis is over?

If possible, I would like to go up north again. Preferably to the Russian part, because that was not possible before. I want to go there. And go kayaking down the coast.

Myrtle Simpson – a living legend

C. L. · Crossing Greenland, alpinist and “mother of Scottish skiing”: The Scottish Myrtle Simpson looks back on a life full of adventure. She was born in 1930 in Aldershot in the English county of Hampshire, her early childhood was spent as the daughter of a British officer in India, and after the Second World War she lived in Edinburgh until she moved to the Scottish Highlands because of its mountains. After an expedition to the Andes in 1958, she achieved her greatest goal alongside her husband and two other expedition partners in 1965: crossing Greenland from east to west in 36 days; on foot, on skis and being the first woman to do that. Four years later, the attempt to reach the North Pole failed. In the 1960s and 1970s Myrtle Simpson – mother of four children – established herself as a book author. In 2017, Prince William awarded her the prestigious “Polar Medal” – 60 years after her husband and expedition partner had received it.

The film “A Life on Ice” portrays Myrtle Simpson’s life and her expeditions. It won several awards, but due to the Corona crisis it could only been watched online at most festivals.